She Who Tells a Story: Women Photographers from Iran and the Arab World, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 27 August 2013 – 12 January 2014.

On view this fall at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts is She Who Tells a Story, an exhibit featuring the work of female photographers from Iran and the Arab World. Curated by Kristen Gresh, the museum’s Estrellita and Yousuf Karsh Assistant Curator of Photographs, the exhibit features individual pieces and series from twelve artists.

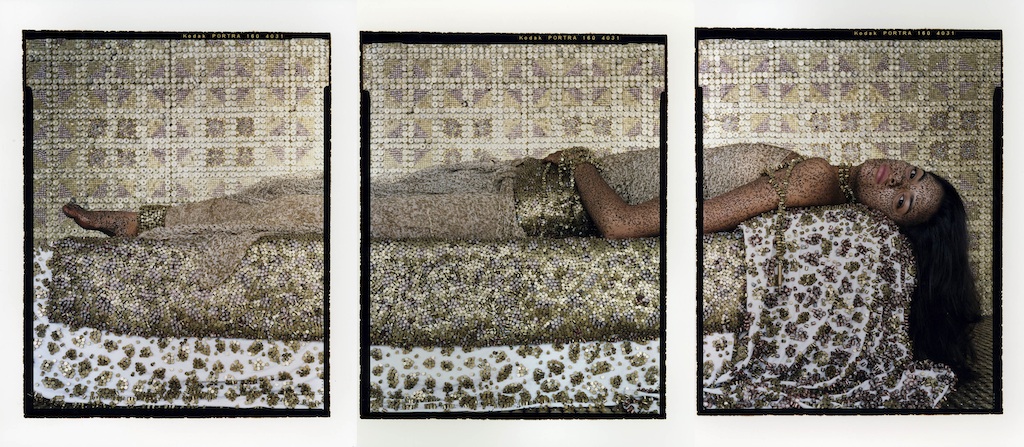

In an introductory video on the museum’s website, Gresh explains that She Who Tells a Story is the first exhibit of its kind in the United States, and the first time that the work of these artists has been shown together. The works compose a broad thematic spectrum, from representations of veiling and female identity to daily life in wartime. Also expansive is the range of photographic approaches, from Shadi Ghadirian’s sepia-toned Qajar series to Lalla Essaydi’s glossy triptych of a woman reclining on bullet casings, worthy of a magazine cover (from Bullets Revisited, 2012).

[Laila Essaydi`s Bullet`s Revisited #3 (2012). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of

[Laila Essaydi`s Bullet`s Revisited #3 (2012). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of

Miler Yezerski Gallery, Boston; Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.]

The museum has compiled biographical essays and reproductions of the artwork from the exhibit into an accompanying catalogue, a volume that describes the collection as a mechanism for “confronting nostalgic Western notions about women of the Orient and exploring the complex political and social landscapes of their home regions.”

The exhibit’s statement of purpose, however, creates a curious dualism that allows only two possibilities in Middle Eastern art: “nostalgic,” romanticized artwork, or work that displays “political and social landscapes” that are forever embattled and riddled with conundrums. This binary, far from groundbreaking, follows the conventional framework through which the Middle East is apprehended: it is either Orientalized or hyperbolically complicated. In fact, the same framework dichotomized another recent art exhibit, Rutgers University’s Fertile Crescent multi-venue program of 2012, which featured a few of these same photographers. One of the curators of Fertile Crescent, Judith K. Brodsky, told the New York Times at the time that the exhibit controverted the sexualized “Western” perception of Middle Eastern women.

Unfortunately, the result of such undertakings is yet another rescue attempt, a curatorial framework that “allows” women of the Middle East to “tell their own stories,” or prove their social merit by depicting politically frenetic or war-torn scenes. Such a lens does nothing to “normalize” artwork from the Middle East.

In fact, it is possible that the very act of curating the photography of “Middle Eastern women” is a further estrangement: It reifies categories (both a geographic one and a sexual one) that seem unnecessary in the realm of art. An exhibit of photography taken by women from Iran and the Arab world that is not centered on a particular theme or subject seems to suggest that there is something distinctive about female photographers from the Middle East as such that merits isolating (or perhaps haremizing?) their work from that of male photographers, or from photographers from any other region of the world who take up similar themes.

On the other hand, most of the artists featured in She Who Tells a Story attempt to erode the false dichotomy and take up more nuanced forms of representation. A notable approach is Rania Matar’s A Girl and Her Room (2010), portraits of young Arab women in their bedrooms—from Beirut to Brookline, Massachusetts. Matar seems to imply in these photographs that there is indeed nothing remarkable about young Arab women. They share the same accoutrements and clutter: bras hanging from doorknobs, makeup littering the tops of dressers, celebrity posters covering the walls, and piles of clothing and stuffed animals strewn all over the floors.

Gohar Dashti also toys with every-day themes in Today’s Life and War (2008), a series of staged images depicting a newly married couple performing mundane daily activities on a battlefield. In one image, the couple eats at a table in front of an enormous tank whose gun is trained directly on them. The signature image of She Who Tells a Story is Dashti’s photograph of the couple dressed in their wedding attire driving through a bombed-out field with tanks looming in the background. The couple is neither blissfully oblivious nor horrified; their stoic expressions dissuade the temptation to find irony in the composition, rather than appreciate the perennial coexistence of domesticity and armed conflict.

Like Dashti, Shadi Ghadirian employs staged subjects in her set of Qajar photographs (1998), portraits of women in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century settings with anachronistic—or subversive—props, like stereos, Pepsi cans, or banned reading material. Ghadirian has explained in interviews that the juxtaposition is meant to invoke tensions between traditionalism and modernity. The tension is an uncomfortable one; the women in the portraits seem to regard their illicit accessories with unease or indifference. “This conflict between old and new is how the younger generation are currently living in Iran: we may embrace modernity, but we`re still in love with our country`s traditions,” Ghadirian told the Guardian in a recent interview.

[Shadi Ghadirian`s untitled from the Qajar Series (1998). Image copyright the artist.

[Shadi Ghadirian`s untitled from the Qajar Series (1998). Image copyright the artist.

Courtesy of the artist and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.]

In striking contrast to this technique is Iraqi-born Janaane Al-Ani’s aerial footage of desert topography, Shadow Sites II (2011), part of a sequence that examines “the real and imagined landscapes of the Middle East.” Al-Ani’s video installations were on view at the Smithsonian Institution last year. Shadow Sites II features aerial footage of man-made edifices dwarfed by immense desert landscapes, a view that seems to suggest their insignificance. Coupled with the drone of an airplane engine as the video’s only sound, the aerial perspective also suggests surveillance or military reconnaissance, particularly that of the United States. Among the work featured in She Who Tells a Story, Al-Ani’s is alone in addressing the aggressive, supervisory role of the United States in the geography of the Middle East.

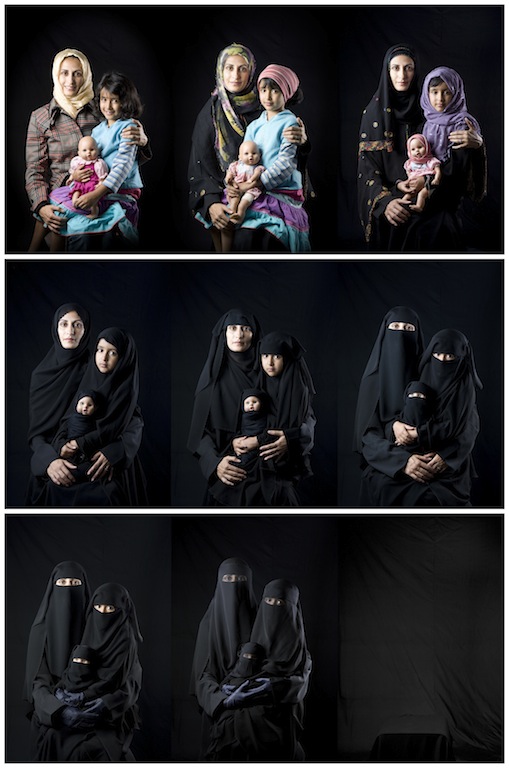

Yemeni photographer Boushra Almutawakel addresses questions of veiling in Mother, Daughter, Doll (2010), a series of nine images depicting a woman with a young girl sitting on her lap, while the girl holds a doll on her own lap. In the first photograph, only the woman wears a scarf around her head. In each successive image, the woman, child, and doll are more covered than in the image before, until all three fade into blackness in the last frame. In isolation, this work seems to suggest the synonymy of veiling and disappearing. This is an implication that turned up in the Boston Globe’s review of the exhibit: the Globe’s art critic Mark Feeny wrote: “The import of the act of veiling could hardly be more revealing.” This is an unfortunate conclusion, because the photographs are part of Almutawakel’s more complex Hijab Series (2008-2012), which is not displayed in its entirety in this exhibition.

[Boushra Almutawakel, Mother, Daughter, and Doll (2010). Image copyright the artist. Museum purchase

[Boushra Almutawakel, Mother, Daughter, and Doll (2010). Image copyright the artist. Museum purchase

with funds by Richard and Lucille Spagnuolo. Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.]

The Hijab Series is a provocative collection that interrogates veiling from a variety of angles, including a sequence called What If, in which a man and a woman sit side-by-side and the woman becomes less covered while the man is progressively veiled in each image—in the last frame, he wears a full niqab. Another piece in the Hijab Series is an examination of traditional menswear: in an image called Ghutra, a woman poses for a portrait wearing a thawb, bisht, and keffiyeh. The net effect of the series is the smudging of the binary rubric through which veiling is typically addressed. Almutawakel’s series not only stretches the continuum between the imaginary poles of secularism and “traditionalism” or “religiosity,” but introduces additional dimensions to the discussion, including nationalism and immigration: another inclusion in the Hijab Series is a woman whose hair is covered in red material as she drapes a French flag over her forearms.

Another provocative inclusion in She Who Tells a Story is Iranian photographer Newsha Tavakolian’s series titled Listen, portraits of women singing, eyes closed, before a sparkling backdrop. Their unheard songs elicit the reality that these women are not permitted to perform or produce albums in Iran.

Even inside the curatorial framework of “combating Orientalism,” most of the individual works featured in She Who Tells a Story do manage to convey images that work to normalize the experiences of women from the Middle East, although this remains an irksome category. What is regrettable is that the exhibit’s raison d’être actually accomplishes the opposite, and poses a distraction from art that belongs alongside that of other great photographers of the world—male and female.